2019 marked the 200th anniversary of the immigration of 180 Welsh men, women and children to New Brunswick and the establishment of the Welsh settlement of Cardigan, located 25 km north of Fredericton. The Central New Brunswick Welsh Society and the New Brunswick Welsh Heritage Trust sponsored numerous activities throughout 2019 to celebrate the bicentenary, one of which was the publication of short narratives aimed at helping us understand the stories of the Welsh settlers. The narratives were based on research gleaned from a multitude of sources, including Dr. Peter Thomas’ landmark book Strangers from a Secret Land, census data, vital statistics, newspaper accounts, land registry documents and many other collections that have been indexed and shared on-line. We did our best to accurately portray the life and times of the Welsh settlers but because our research is a work in progress, there may be errors and omissions. All contributions of new information will be gladly received!

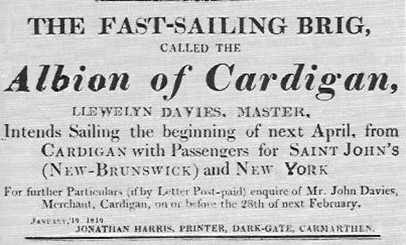

THE ALBION

The Albion, owned by the Davies family of Cardigan, was built in 1815 in Milford Haven by William Roberts, brother-in-law to Captain Llewelyn Davies. The Albion was the first Davies ship built specifically for the high seas. It was the largest of the Davies ships, measuring 72 feet from end to end and 22 feet 3 ½ inches at its widest point.

The Albion was a brig, a sailing vessel with two square-rigged masts. Brigs were fast and maneuverable, which made them the ship of choice for naval warships and merchant vessels. Its shortcoming was its need for a large crew to handle the rigging, along with the need for a skilled captain to effectively manage sailing into the wind.

By the early 1800’s the brig, was the standard cargo ship. The timing of the initial launch of the Albion in 1815 could not have been better for the Davies family, as the end of the Napoleonic Wars meant safer sailing that encouraged trade. The Albion became active in the lumber trade between British North America and Wales. In 1818, in response to an increasing demand for passage to North America, the Albion made its first passenger run to New Jersey where Captain Llewelyn dropped-off eighty Welsh immigrants and picked up lumber for the return trip to Wales. After its delivery of 180 settlers to Saint John in June 1819, it began travelling the waters around Wales and Ireland. In November 1819, however, it was lost off the coast of Ireland during severe weather– all on board perished. Captain Llewelyn Davies was not yet 30 years old.

WE CAN HELP YOU GET TO WHERE YOU WANT TO GO...

......advertised the Davies family, merchant mariners based out of Cardigan, Wales. Following a successful run to America with Welsh settlers in 1818, the Davies family decided to make another delivery of immigrants the following year, this time stopping first in British North America. Given the poverty, unemployment in Wales, there was a great demand for berths for emigrants. So, in January and February 1819 a handbill was circulated in both English and Welsh throughout south-west Wales, advertising the April sailing of the Albion to Saint John. A similar advertisement was published in the Carmarthen Journal, beginning on February 26th and running for three weeks. As a result, the Albion was full to capacity and on April 9th, Captain Llewelyn Davies set sail from Cardigan with a full load of 180 passengers. They arrived in Saint John, New Brunswick on June 11, 1819. Captain Davies, however, did not sail on to New York as previously advertised. In mid-July he headed back to Wales with a hold full of timber, leaving all his passengers in Saint John, whether this was their intended destination or not!

A BUSTLING PORT

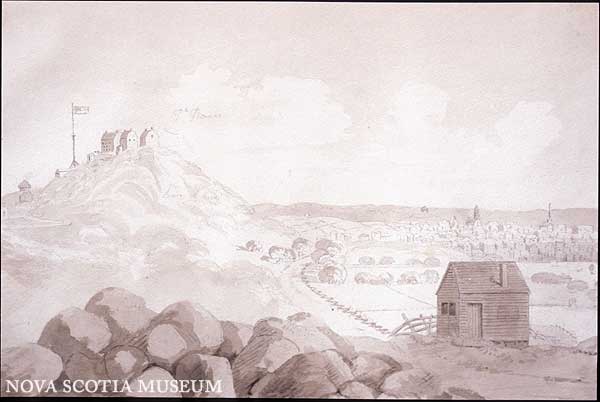

The Albion was headed for the busy port of Saint John, New Brunswick. Saint John was first visited by French explorers in 1604. It was primarily a trading post and military garrison for both the French and the English until the influx of more than 14,000 Loyalists in 1783. In 1785 it became incorporated by Royal Charter and is Canada’s oldest incorporated city.

The Welsh settlers disembarked from the Albion on June 11, 1819. What they saw was a bustling port city, growing rapidly due to immigration and struggling to meet the needs of their burgeoning population. In 1819 there were 6,000 citizens, with the most influential citizens being prominent Loyalists and their children along with a powerful merchant class who were mostly Scotsmen. The harbour registered passage of more than 500 vessels that year, some bringing the more than 7,000 emigrants who arrived in Saint John in 1819. The shipyard and timber trade were booming. There was plenty of work for hard-working young Welshmen and women. And, despite their odd dress and even odder language, the sober Welsh immigrants must have compared well against the recently arrived soldiers of the Royal West Indies Rangers who, being discharged from service, were spending their pay packets in the local taverns and creating a significant disturbance!

THE SEAT OF GOVERNMENT

Prior to the arrival of the Loyalists in 1783, there were only three habitations in Fredericton, a log cabin and two frame houses. In the summer and fall of 1783 many Loyalist families, most of whom were members of disbanded Loyalist regiments, were sent to St. Ann’s Point (Fredericton), to take up land. The new residents successfully petitioned Governor Parr to have the new town surveyed in 1784, coinciding with the separation of Nova Scotia into two parts and the creation of the province of New Brunswick. Governor Thomas Carleton, the first governor of New Brunswick, arrived in November 1784 at which time he and his Executive Council spent the majority of their time dealing with land issues – allocating land for public use and grants to the many Loyalists. In January 1785 he moved permanently to Fredericton, declaring the the town the provincial capitol and thus, making it the centre of government, the university and the Church of England. In addition, large military units were garrisoned in the town on a large tract of land in what is now the city centre.

Fredericton grew slowly. By 1819 there were less than 2,000 souls living in the young town, which only in that year assigned names to its main streets. However, there was a provincial assembly building, an Anglican church and meeting houses for the Baptist and Methodist congregations, a college, a public market house, a county courthouse and a jail along with a number of military buildings. There were several fine houses surrounded by large tracts of land owned by the wealthy and privileged government officials, most of whom had been appointed into their positions due to their Loyalist background. There was a grand mansion for the Governor located on the outskirts of the town. Altogether there were just 200 residences. But commerce was flourishing, creating a new class of prosperous and influential businessmen. Can you imagine the impact made by the arrival of 150 destitute, oddly dressed, Welsh speaking, religious dissenters on such a small, conservative population!

THE SURVEYOR-GENERAL

The Welsh settlers arrived in New Brunswick without any idea about how to acquire land. Luckily, their arrival coincided with the appearance of Anthony Lockwood, the newly appointed Surveyor-General for the province. Lockwood had been appointed by the Crown, despite the fact that Lieutenant Governor Smyth had recommended George Shore, then acting surveyor general, for the post. This was a choice position as it came with membership to the Executive Council. Lockwood was well- aware of the fact that his appointment was unwelcome. And so, perhaps to curry favour with the bureaucrats in Fredericton, he undertook the challenge of assisting these sober, hard-working and deserving Welsh immigrants to settle in the province. He helped the Welsh settlers move upriver where he assisted them in petitioning the Executive Council for land ‘back of the Nashwaaksis Stream about seven miles from the Mills, and in the direction of the Tay.’ He personally visited the site of the new settlement and signed tickets-of-location for the new settlers. He contributed generously to the Emigrant Society, established to assist the Welsh settlers while they were constructing their first homes.

The Office of the Surveyor General was a demanding workplace, being responsible for ensuring that land was mapped properly, and that ownership was recorded and tracked. The Office was also responsible for surveying county and parish boundaries as well as roads. Anthony Lockwood threw himself energetically into his new job, accomplishing an amazing amount of survey work in his first few years. By 1823 his frenzied approach, however, had taken its toll. His behavior became increasingly erratic, culminating in May in him riding about the streets of Fredericton, firing pistols and declaring that he had been ‘called’ to take over government. He was jailed and declared mentally unfit. Eventually he and his family returned to England where he suffered from bouts of insanity until his death in 1855. Dr. Peter Thomas’ book, Master & Madman: The Surprising Rise and Disastrous Fall of the Hon Anthony Lockwood RN, provides a detailed look at the life and career of Anthony Lockwood, the 'lunatic' who was instrumental in the establishment of the Welsh settlement of Cardigan.

LOCATION TICKETS

A Ticket-of-Location was provided by the Surveyor-General allowing the bearer to occupy and improve a particular lot of land. On July 21, 1819 the Executive Council heard a petition and a supplementary petition from 25 Welsh immigrants, asking for land ‘back of the Nashwaaksis Stream about 7 miles from the Mills, and in the direction of the Tay’. The petitions were approved and the first tickets-of-location given to the Cardigan settlers were issued on July 26, 1819. Married men were given 200 acres while single men were given 100 acres. Each settler was then expected to build a cabin and clear and cultivate the land within a few years. He would then petition the Executive Council for his land, describing his family situation and the state of improvements made on the land. The grant required the payment of a quit rent, the amount of which was based on the number of persons and the number of acres included in each grant. Many settlers joined together and appointed one main grantee in whose name the grant was made, but each grantee was legally bound to the terms of the grant. The terms to be upheld were: 1) the payment of two shillings for every 100 acres to be paid on mid-summer day beginning two years after the date of the grant and forever after; 2) for each fifty acres, the clearance and cultivation of three acres if the land was arable, or the drainage of the same amount if the land was swampy; 3) the sustenance of three cattle if the land was wilderness; 4) the excavation of a stone quarry if the land was rocky; and 5) if the land was unfit for agriculture, the construction of a good dwelling house. Proof of compliance to the grant conditions had to be provided to the Executive Council within three years.

David Griffiths received his location ticket in July 26th, 1819 for Lot 9 on the west side of the Cardigan settlement. He petitioned for his land in December 1827, having built a house and a barn and cleared 12 acres. He received his land in 1831 in a grant where John Evans was the main grantee and there were five others – David Griffiths, Rees Jones, John Davis, John Edwards and James Evans.

THE EMIGRANT SOCIETY

The Welsh immigrants who arrived in Fredericton in July 1819 were woefully unprepared to be settlers. They had little or no money, few possessions and no knowledge of how to create a homestead in the forested wilderness. Despite the fact that the process of locating land to the settlers had begun, it was clear by mid-August that the Welsh families would need help. On August 10th a meeting of the inhabitants of Fredericton was held at the Jerusalem Coffee House where it was decided to form a new organization, named the Cardigan Society, to assist the Welsh families. Membership was by subscription. More than £76 along with promises of tools, clothing and provisions were raised. A week later the Cardigan Society defended itself in the local paper, saying that their intent was not to ‘make them idle, or to damp their exertions by giving too much’ but to ‘assist and stimulate industry’. They stated that it was evident that the settlement could not be established without help. They also responded to the criticism that they were only helping the Welsh settlers, saying that if additional funds were raised, other immigrants would be helped. By that time, they had raised £135 and collected a lot of clothing.

The Cardigan Society continued to report on the progress of the Welsh settlers throughout the remainder of 1819. The newspaper accounts provide much information on the state of the Welsh families and their progress in Fredericton. They also indicate that there was not universal agreement of the need to help the immigrants. In November the Cardigan Society was replaced by the Fredericton Emigrants Society, led by the current and future Chief Justice of the province. Indeed, the membership of the new Society comprised the elite and powerful in the city.

THE ‘HUTS’

The first task of the settlers was to construct housing for their families. The August 17th edition of the Royal Gazette reported that it would cost a minimum of £8 to build each shelter. These ‘huts’ were described as being constructed of ‘round logs 15 feet long, laid up 7 or 8 feet high, covered with bark; a door and one small window; the chimney of mud and sticks, or stone’. The following week the paper reported ‘A number of the Welch settlers were fitted out last week to commence their settlement. A person acquainted with constructing log houses has been employed to instruct and assist them; a quantity of bark has already been procured, and other preparations made to commence building immediately; and there is no doubt but in a few weeks a number of families will be comfortably sheltered.’

Comfortable may have been a bit of an overstatement. These first cabins were generally crude and cramped, having an earthen floor and only one room in which to live and sleep. The roof was flat, made with overlapping split logs, covered with bark and then fir or spruce boughs. Fortunately, there was plenty of building materials available in the Cardigan wilderness. But those nine families who wintered in their new cabins in Cardigan must have found them lacking when compared to the warm homes that they had left in Wales.

THEY ARE VERY DESTITUTE

The Welsh families must have wondered if they had gone from the frying pan into the fire by leaving Wales. They arrived in Fredericton where it became apparent that they would need some assistance as they were ‘very destitute’ and were ‘straggling through the Streets or crowded into Barns’. By the end of August, many were working on clearing their land in Cardigan despite being ‘straightened for Provisions’. A call for food was made to feed the hungry settlers. On September 21st the Royal Gazette reported ‘they are very destitute, and have large families of helpless children, it is evident that without further assistance they must nearly perish with cold and hunger the ensuing winter.’

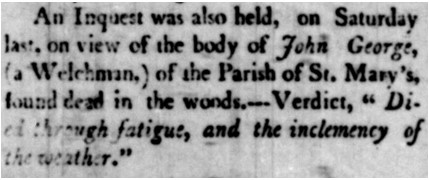

In November it was reported that ‘they have hardly the second meal for their families, have no credit, and are most of the time half starved. It is probable that the death of the man who perished in the woods on Thursday last, was occasioned by as much as the want of sufficient nourishment as by cold and fatigue.’ By the end of the month, a Committee was appointed to examine the condition of the Welsh families. They were found to be, almost without exception, poorly housed and unprepared for the harshness of the oncoming winter. The situation of William Richards’ family portrays the harsh conditions that the families were experiencing:

‘The situation of one Welch family, (William Richards’) consisting of the parents and four children, all lying in a most miserable situation, under the influence of a raging fever, particularly attracted the attention and commiseration of your Committee, and they presumed upon the approbation of the meeting, in taking immediate steps for their relief, by purchasing a Stove, and preparing a vacant house above the town, (which was offered by the Honourable Mr. STREET) for their reception—one of the family, (a child 14 years old) your Committee find, is since dead.’

FROM DAVIS TO REES

Daniel and Hannah were probably married already when they arrived in New Brunswick, although they did not yet have any children. Daniel was likely the son of Daniel and Ann, or perhaps the brother of John G. Davis. Daniel was 21 and Hannah was 35 years old. Hannah’s brother John and his wife came as well but initially went to the Waterborough parish area near Grand Lake with two other couples from the Albion (both named John Jones).

Peter Thomas says that the Rees family legend is that Daniel Davis changed his name to Daniel Rees because there were too many Davis’ and he moved to Newcastle Creek. Rees was Hannah’s surname. Whatever the reasoning, Daniel and Hannah did indeed change their name to Rees.

Daniel and Hannah initially lived in the Hamtown/Cardigan area, perhaps with Daniel and Ann? They had three sons, all born in New Brunswick. Henry was born in 1820, Peter Owen in 1825 and Daniel J. in 1828. They were certainly in the area in 1825 when the great Miramichi fire swept through, forcing Hannah to take refuge in Carleton Lake with baby Peter Owen in her arms. However, rather than stay in the area, they petitioned for land in Canning Parish, Queens County in 1826. This area later became part of Sunbury County, first Sheffield and then Northfield parishes. His petition said that he was 28 years old, from South Wales and had been in the province for seven years. He was married and had two children. The land was to be 300 acres above the grant to Lewis Albright. He was granted his land in 1832.

In 1851 the Census reported Daniel Rees (52) and Hannah (67) as living in Sheffield Parish, which was split in 1857 with the new parish being named Northfield. Their sons lived with them. Daniel Jnr. was not yet married, but Henry (30) and Peter O. (27) both had wives and children living there as well.

In 1861 Daniel (62) and Hannah (77) still lived on their homestead. Their sons Henry and Daniel also lived on the homestead. Hannah passed away sometime in the 1860’s. Land transactions indicate that Daniel divided up his property (but not evenly) through sale of portions of it to his children.

In 1871, Daniel was living on his land in Northfield Parish, with his sons and grandchildren nearby.

Daniel died in February 1873. His obituary in the Christian Visitor read ‘d. Northfield, 4th ult., Daniel REECE, age 75, left three sons. He was a native of Wales. He professed religion several years ago and united with the Newcastle Church (Queens Co.) The funeral was attended by Bro. Simpson.’

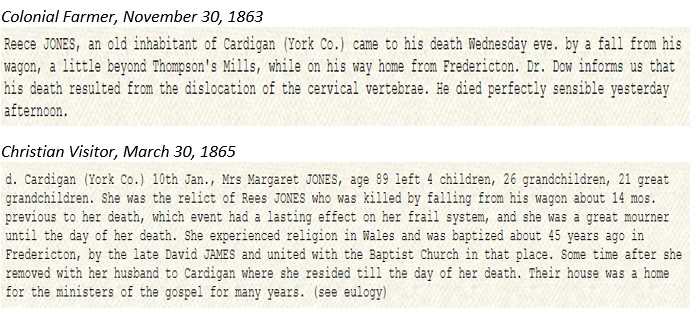

MARGARET RICHARDS AND REES JONES

Margaret Richards left Wales on the Albion with her husband and 6 children. Her daughter, Iona, died on the voyage to Saint John. In November 1819 a committee appointed to investigate the condition of the Welsh families, reported that William Richards and his family were ‘lying in a most miserable situation, under a raging fever’. The committee bought them a stove and found them a vacant house in which to live, but one of the children, a 14-year old, died. William Richards died in 1821 or 1822 without having done anything to his land in Cardigan. Perhaps he had never recovered from the illness experienced upon arrival. He left Margaret with four children. She continued to live in Fredericton with her children until she remarried.

On November 1, 1823, Margaret married Rees Jones. It was not unusual in those days for widows to remarry. What was unusual was that Margaret was 47 years old when she remarried – Rees was 24.

Rees Jones was also a passenger on the Albion. He arrived when he was 19 years old. It appears that his parents did not accompany him as his marriage record says ‘with consent of guardian’. He may have been related to Jonathan Jones who witnessed his marriage. Or was it Margaret, a widow, who had to have consent from a guardian?

Margaret held the location ticket for Lot 8 West that had been originally issued to William Richards. Rees immediately set to improving this land. He built a cabin to which they moved in 1824 and a barn, and by the time he petitioned for his land in 1826, he had four acres cleared. His petition was not approved immediately. He was asked to provide additional information on the children of William Richards, which he did, stating that since William had made no improvements to the land, his children would have no claim to it. He said that he would never have settled on the land if he had known there would be an issue as there was plenty of other land in the area available to him. He stated that he had settled on the land at the request of his wife. There was an additional note from John Robinson, Justice of the Peace, saying that Rees Jones was a hardworking man and that the petition was just. Rees was granted his land in April 1831.

Margaret and Rees had no children together, not surprising given her age. But despite their age difference, Margaret and Rees were respected members of their community. Rees died in November 1863 and Margaret in January 1865. They are both buried in the Welsh Chapel graveyard in Cardigan.

SHELBURNE AND CARDIGAN CONNECTIONS

In May 1818 the ship the Fanny arrived in Halifax with 112 Welsh settlers from Carmarthenshire and Cardiganshire. Seventeen adults and 29 children (comprising eight families and a single labourer) moved on, intending to settle on land near Shelburne, Nova Scotia. As with most settlement plans, all did not go smoothly, but by June 7th, 1819 when the Albion arrived at Shelburne, most of these families were beginning to get established in the area.

Some passengers on the Albion disembarked to join family or friends in Shelburne. At least three families settled permanently in the area, leaving descendants and public records to witness their settlement. These families were David and Margaret Davis and their seven children; John and Mary Harris and their eight children; and David and Anne Jenkins and their four children. Others may have also disembarked but subsequently moved elsewhere.

Some of the Fanny passengers eventually found their way to the Cardigan area. John and Esther Thomas and their children arrived in Cardigan in 1821 to take up lot 15 on the east side of the Cardigan road. They had been one of the original eight families that settled in Shelburne.

The Owens brothers, Enos and John, also left Shelburne to settle in Cardigan. While John and Catherine were one of the original eight families and had settled on a lot of land, it appears that Enos and family did not arrive in Shelburne until late 1819 or early 1820. Perhaps Enos did not find land that suited him in the area, because by May 1822, Enos had moved his family to Cardigan where he received a location ticket for lot 16 on the west side of the Cardigan road. In June his brother David arrived from Wales with his family, locating on lot 4 east. John and Catherine joined the Owens brothers soon afterwards, receiving their location ticket for lot 16 east in February 1823.

William Morgan, a single man, also arrived in 1822. It appears that although he was listed as intending to go to Shelburne, he never actually went there. He likely remained in Halifax until he came to the Cardigan area where he received a ticket of location for Lot 3W south of ‘Hamboro, Cardigan’. This lot is located just above what is today the McFarlane Road.

JOIN US!

Despite the hardships they faced, the Cardigan families must have written optimistic letters to their friends and families in Wales which encouraged them to make the long trek across the Atlantic.

In 1822 Reverend Dafydd Phillips visited the community with a view to purchasing land on which he and his family could settle. Although Reverend Phillips changed his mind, several families who had travelled with him from Wales established themselves on land in the area. William Sansom and Mary Nichols were a young couple with an infant son, presumably connected to someone in the area. They received a location ticket for lot 18 on the east side of the Cardigan road. David Owens came with his wife and children, inspiring his two brothers, Enos and John, to come to Cardigan from Nova Scotia later that year. Evan George and Martha Phillips came with their young children to join Evan’s family. He joined his brother, David, who was located on lot 3 on the west side of the road next to his father and siblings.

The Richards brothers, Titus and William, also came with Reverend Phillips. They bought lots 1 and 2 on the west side of the road in Hamtown. Thomas Richards and family were also part of this group, perhaps a brother to Titus and William. He was located on the northern half of lot 1 on the west side of the road in Cardigan. Another set of brothers, David and William Phillips, also arrived together in 1822. They most likely had accompanied Reverend Phillips as well, perhaps they were related to him. William had a family and was eventually granted lots 13 and 14 on the west side of the road in Cardigan. David settled in Fredericton, although he maintained close ties with the Welsh families in Cardigan.

Other families joined the budding Welsh community. William Morgan arrived from Nova Scotia in 1822 to be located on land in Hamtown. His brother David immigrated in 1829. William Thomas, who had arrived on the Albion but not taken up land initially, settled on land in Tay Settlement in 1824. William and Thomas Davis immigrated in 1830 to settle in Hamtown; Richard and Hannah Williams settled in Tay Settlement in that same year; and James and Maria Evans came at an unknown date but were on their land in Woodlands by the mid-1830’s. William Harris arrived in the early 1830’s. He became the pastor at the Baptist chapel in Cardigan.

Within a decade of felling the first tree in Cardigan, 20 more Welsh families had joined the original settlers. Nearly every plot of land in the area was occupied by one of the Welsh families or their children.

‘THERE ARE MANY CHILDREN OF THE WELCH DECENT’

In the 1820s small rural communities were expected to build their own schools, hire a school master and raise the money for the master’s salary. Teachers were licensed, with approval for the license granted by the Lieutenant-Governor. By 1827 the citizens of Cardigan were ready to support a school in the community.

On March 20, 1827 Thomas Saunders applied for a teacher’s license stating ‘That the said Settlement consisting of from thirty to thirty-five families there is no School that there are many children of the Welch decent most of whom cannot speak English, that your petitioner can speak both English and Welch, that the Settlers have engaged with petitioner for thirty-two pounds per year they having built a School House petitioner has a recommendation from two of the Trustees of Schools for that Parish and prays your Excellency will be pleased to grant him Licence to keep such School.’

Thomas Saunders was 18 years old when he arrived on the Albion in 1819 with his parents, David and Elizabeth, and his siblings. When his family moved upriver to be located on land in the new Welsh settlement, Thomas remained in Saint John, presumably having found employment, until sometime in 1820 when he moved to Lincoln Parish. For some reason there were a few young Welsh settlers living in Lincoln Parish near that time, evidenced by the marriage records (William Griffiths and James Evans both record Lincoln Parish as their residence in 1821 when they married). Sometime in 1821 he joined his older sisters, Martha and Frances, in Fredericton where he lived until he joined his parents in the Cardigan settlement in 1824.

Thomas was granted his teacher’s license that year, and in every subsequent year until March 1833 when he stopped teaching to get married and take up farming on his father’s land.

THE SAILING OF THE ELIZABETH

Not everyone was satisfied with their new life in Cardigan. On November 19, 1832 the schooner the Elizabeth arrived in New York harbour from Saint John, NB. The only passengers were four Welsh families and young Mary Owen, a 19-year old seamstress.

Two families were those of the Richards brothers, William and Titus, who had arrived in 1822. The brothers had purchased land in Hamtown where they settled into farming. In addition to farming, William was appointed the road surveyor for the area in 1823. At the time of sailing, the two families had 10 children between them, ranging from 1 to 18 years of age. The Richards families did not remain in New York City. By 1840 they had moved to Franklin County, Ohio where they lived out their lives. William and Mary and Titus and Hannah Richards are all buried in the Greenlawn Cemetery in Columbus, Ohio.

John and Martha Griffiths and their eight children also travelled on the Elizabeth. John and Martha had arrived on the Albion in 1819 and settled on land in the second tier in Hamtown. It appears that John had gone ahead of the family to find a home for them, and then returned to take them back to New York City on the Elizabeth. Their neighbours, Benjamin and Rachel Phillips and their two young daughters travelled with them. Benjamin and Rachel had arrived in 1822 and purchased land in Hamtown. It is difficult to determine if the Griffiths family stayed in New York, due to the many public records for ‘John Griffiths’. However, Benjamin and Rachel lived out their lives in Manhattan.

Other families moved on as well. In the early 1830s several families moved to New York City – Jonathan George, David and Elizabeth Davis, John Roberts, Richard and Martha Williams, and David and Maria Richards. James and Louisa James moved to Long Island, New York. The sons of William John all moved away, with David and Benjamin changing their name to Jones after they settled in Ontario. Griffiths Jenkins moved to Kansas where he remarried and spent his life farming. David and Martha Morgan moved to Minnesota. Cardigan daughters married and moved to other parts of the province, to Nova Scotia and the US. And others, just left the Cardigan area for parts unknown.

EVENTUALLY THEY PROSPERED

Although the summer of 1819 was hot, the cool weather came early. The first frost along the lower Saint John River occurred in early September. The river was partially frozen by early November and fully frozen by the first week of December. The families of William John, Jonathan George, John Evans, William Davies, David Davies, Aaron Smith, David Lewis, James Evans and John Williams spent a cold and hungry winter in their huts in Cardigan. The Welsh families in town were miserably housed in huts, barns and sheds. In January there was a news story of a Welsh family found frozen.

But spring finally arrived, and the Welsh families worked hard to establish themselves. The 1820s saw the immigration of twenty more Welsh families to the Cardigan area. A Baptist chapel, a grist mill and a schoolhouse were built. Land was granted and the next generation of immigrants spread to neighbouring communities. Some moved to New York, Kansas, Ohio, Minnesota or Ontario, while others moved into ‘town’ to establish successful businesses. Cardigan prospered and by the 1870s there were schools, lumber and grist mills, a blacksmith, a shoemaker, a Baptist chapel and a Congregational church, and a post-office in the area.

Over the past 200 years, the descendants of the original Welsh families prospered and spread across the country, although some still live in Cardigan. They left the farms to become doctors, engineers, soldiers, airline pilots, nurses, teachers, entrepreneurs, accountants, pharmacists, professional athletes, RCMP officers and university professors. They served their country honourably in two world wars and continued to serve in Canada’s military. Their keen sense of community, so much a part of their Welsh culture, led them to serve their fellow citizens at City Hall, in the Legislative Assembly, in hospitals, schools, government offices, on school boards, with civic organizations and most recently, as Lieutenant-Governor of New Brunswick.

Today Cardigan looks very different. Like most rural communities, the post-WW2 industrialization saw the end of small family farms and indeed, much of the land cleared so painstakingly by the original settlers has reverted to forest. The Baptist Chapel and graveyard has been declared an historic site, maintained by the great, great, great grandchildren of the original settlers. Services are held in the Chapel in June to commemorate the arrival of the Albion and in October to give thanks for the perseverance of our ancestors.